This month we are taking you to a country where not many of you have been: Kyrgyzstan sounds mysterious and unknown to most of us. Please welcome our guest, Mohira, who will guide us through this extraordinary journey of discovery.

Can you introduce yourself please?

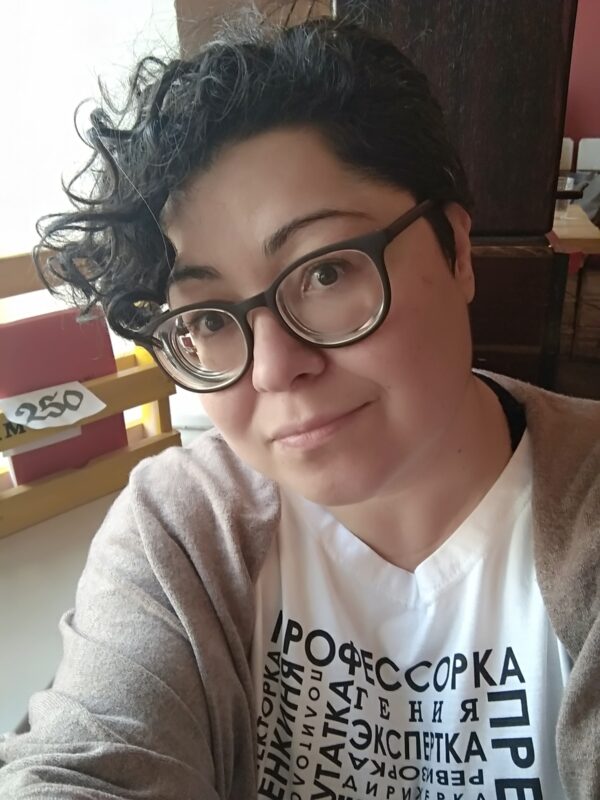

My name is Mohira. I am a queer woman living and working in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, but I was born in Tajikistan and lived in Uzbekistan for a significant part of my life as well. A social scientist by training, I teach at a local university as my main occupation. Apart from that I also work with a local LGBTQ+ organisation "Labrys" on various educational and research projects. And I am also on the Board of EL*C (recently renamed as EuroCentralAsian Lesbian* Community). It is very important for me to combine my professional life with activism and art.

Sounds impressive. Now please tell us a little bit about Kyrgyzstan. How would you summarize the general situation of the LGBTQ+ community over there?

Kyrgyzstan can be considered the most liberal state in the region when it comes to LGBTQ+ rights. Unlike in neighbouring Uzbekistan, for instance, it is not illegal to be gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender in Kyrgyzstan. LGBTQ+ organisations like Labrys are officially registered and can work openly. Yet, while we have achieved some gains (with regard to the transgender rights, for instance), LGBTQ+ activists work in the environment of growing homophobia and state-supported misogyny.

This conservative turn is part of a global trend, and local conservative and nationalist forces are connected to their counterparts across the world. Since 2014, for instance, a broad coalition of civil society organisations in Kyrgyzstan have worked to prevent the passing of a homophobic "anti gay propaganda" bill copy-pasted from the Russian equivalent (which in turn was inspired and enabled by Evangelical pastors from the United States, who have also pushed a homophobic bill in Uganda). In this environment many queer people have to live double lives - some gay men and lesbian women even enter into fictitious marriages to placate their relatives. Some lesbians are subjected to corrective rape and forced into marriage. Generally, it is not easy to be a woman in Kyrgyzstan and to be a queer woman is doubly challenging.

What’s the situation in Bishkek, the capital?

Very few lesbians live openly and are publicly out. For many, going away from one's family is the only option of living a more open and fulfilling life. This is in large part due to the economic dependence of women on their kin, whereby one's survival depends on the support from one's familial network. LBQT+ women are not visible, and in the public eye LGBTQ+-issues are framed through the prism of Western LGBTQ+ movement's preoccupation with marriage. One recent example is this year's 8th March (International Women's Day) March in which Labrys and other LGBTQ+ groups participated (as we always do) carrying rainbow flags and other LGBTQ+ symbols. This event was then covered in many local media as Kyrgyzstan's ''First Gay Pride.” Many 'liberals' showed incredulity asking 'But what do the LGBTQ+ have to do with women's issues?' and even some of the local organisations working on women's rights had to be reminded that some women are lesbians, bi, queer and/or trans.

Can you say a couple of words about lesbian* social life in Bishkek?

Bishkek's only surviving LGBTQ+ bar is owned by a lesbian couple, who see this not as much as a business but as a form of activism. There are a few other places in town that are either owned by LGBTQ+ people or are considered friendly. There are no Prides, but our community is creative and vibrant and we organise numerous cultural and activist events in various spaces across the city, in our community centres, in our flats and as outings in the nature. There are no exclusive lesbian* spaces though - something that we should work on, perhaps.

Finally, it is a major goal for qLit to help increase visibility in the Hungarian LGBTQ+ community, so can you contribute by sharing a memorable coming out stories of yours?

Recently I was invited to speak at an event on LBQ women's leadership in Bishkek, and as I was preparing to open the event I realised that none of the other speakers openly identified as a lesbian* (in fact, a few of them deemed it necessary to 'come out' as straight after my speech). So I did a double coming out - as a lesbian and as a communist; I am not sure which shocked people more.

Also, a few years ago I wrote an article criticising the concept of 'coming out' as the necessary rite of passage for queer people, because of its cis-hetero-normative nature. Instead, I offered to pronounce an International Coming-In Day, whereby queer people invite the 'straights' to come and join us in our wondrous world, to experiment with their sexuality, to have fun with their gender!