It’s obvious that for the sake of the individual’s and society’s mental health coming out should be made possible. What is not discussed in similar depth is the period before coming out when one isn’t even sure what they are mulling over or what exactly they are looking for. Some already know but they are still seeking validation before sharing the news with the world. Outing a questioning, uncertain, vulnerable person can cause deep trauma.

For centuries this much needed space, a space we could call ‘un-closeted’ was provided by libraries. Before the internet it was the library where one could turn to with their questions, and never knew what answers, what stories they would find. As actually checking the book out ran the risk of being outed – who wouldn’t know the feeling of trying to avoid eye-contact with the librarian when checking out a lesbian* book? – it was often better to limit browsing and reading to the confines of the library. I also spent countless hours like this myself, buried in books. Novels, feminist essays, manifestos, autobiographies: in the end the format didn’t matter, as long as I found something to go on it always gave me more leads, more sources to check out. Usually multiple ones.

It’s not all that surprising if we think about it – since literacy became available for women (since the 19th century at latest) a female writer dealing with lesbian* themes of some sort would have known for sure that others were struggling with the same questions she did, so she would frequently refer to other important works in her writing. This way, long before the existence of the internet, a ‘lesbian* world wide web’ reaching over time and space was built. And all my favourite lesbian* writers – maybe surprisingly, at the first glance – were all well acquainted with this web.

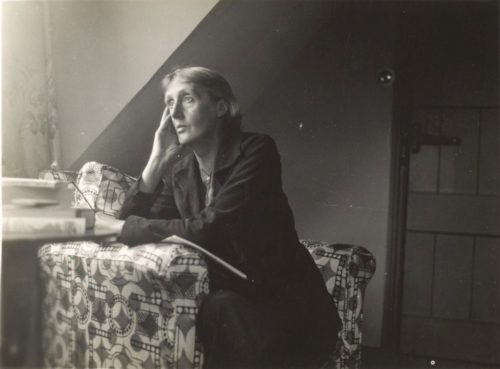

The famous English writer Virginia Woolf is a good example of an LGBTQ+ writer who referred to other important writings in her works and who could navigate the ‘lesbian* web’ very well. For example it was Woolf who made me aware of Aphra Behn, a 17th century writer whose heroines, while not openly lesbian, were very strong and independent, a stark contrast to the norm of her time. It’s also Woolf’s letters that will lead the curious reader to Vita Sackville-West, Woolf’s lover, for whom she wrote the brilliant novel, Orlando. Following the trail we get to Radclyffe Hall, whose novel, the Well of Loneliness caused a scandal while Woolf’s and Sackville-West’s affair was ongoing. Hall was brought to court over charges of obscenity and Sackville-West spoke at her trial (in her defence, of course).

While hiding in the library one will soon realise that (1) questions can have a myriad of different answers and (2) pretty much everyone is a lesbian*. All right, the latter is a bit of an exaggeration, but generally we’ll find - with relief and excitement – that a lot of people we never would have thought were lesbians*, and a lot of novels that count as literary classics feature lesbian* characters and themes. By way of real people I’m talking about the bisexual Frida Kahlo (her recent exhibit in the National Gallery of course wasn’t quick to divulge this piece of information), Rosa Bonheur, the successful 19th century painter, and Greta Garbo. (Really?! Greta Garbo?! When I first heard about it I didn’t want to believe it.) As for books, there’s an important lesbian* subplot in for example Alice Walker’s The Color Purple or Harper Lee’s novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, which is usually cited as a work about the life of Black people – but there’s also Marcel Proust’s avant-garde classic, In Search of Lost Time or Péter Nádas’ master work, Párhuzamos történetek (Parallel Histories), which is also very rarely mentioned as having lesbian* characters or scenes.

Actually, even older classics deal surprisingly frequently with the theme of lesbianism*. Two examples from the 18th century are Choderos Laclos’ novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses (Dangerous Affairs) - a story which, albeit stripped of its lesbian* themes, might be familiar from its 1988 film adaptation, starring Glenn Close, John Malkovich and Michelle Pfeiffer – and what is probably the most widely-read novel of the 18th century, the extremely long Clarissa by Samuel Richardson. The hint at lesbianism* is completely clear in both books, or if not 100% obvious then at least very suggestive, and neither work judges the lesbian* themes.

The comforting conclusion that ‘everyone’s a lesbian* here’ inspired literary expert Terry Castle to publish and anthology on exploring lesbian* themes, called Literature of Lesbianism. What’s really interesting about Castle’s work is that its focus isn’t on lesbian* authors, but the theme of lesbianism*, which is either shown in a positive or negative light in the works discussed. Castle’s anthology makes it clear that female-female love has always been discussed in literature, and not only by female writers.

I would also recommend Castle’s other popular works, like the partly autobiographical collections of essays The professor: A Sentimental Education or The Apparitional Lesbian. Castle realised while attending University that there are a lot of books she must read. She soon fell face first into a heap of lesbian* books, one more exciting than the other, a reading adventure that soon lead to her coming out. Later she became an acclaimed expert on lesbian and feminist literature, nowadays she’s a teacher at the world famous Stanford University of California.

Comic-book artist Alison Bechdel who got popular by her comic series Dykes To Watch Out For and who entered pop-culture knowledge by the so-called Bechdel-test also depicted the character of the lesbian* hiding in the library in a memorable way. In her autobiographical comic Fun Home she describes how the University library made her discover her own identity. Bechdel sees her realisation of being a lesbian* as a direct result of her adventures in the library. Furthermore her realisation was directly followed by a coming out letter to her parents, despite the fact that at the time she had no opportunity to test her discovery in real life. Meaning she neither had a girlfriend or any sexual experience.

Readers need not worry, Alison caught up soon enough - and here the pictures of the comic make the lesbian* audience very happy, unlike certain American highschools, where the comic was instantly banned. I don’t know if this ban still stands, especially since in the meantime Fun Home was turned into an acclaimed musical. Bechdel, just like Castle, joins the ranks of historical women who provide access to the ‘lesbian* web’ for all their questioning brethren. After all, qLit serves the same purpose: a Hungarian space where lesbians* are safe to explore the lesbian* world, and maybe their own identities too.

Translated by Zsófia Ziaja