For many of us, university years are a defining period in our lives. It is when we enter adulthood, becoming independent, and it is when we study what we are really interested in, surrounding ourselves with people who are like us. But being in higher education in today’s Hungary is challenging, to say the least, both for teachers and students. Especially so since the government has bought up most Hungarian universities. Where do LGBTQ people belong, whether they want to study or work in higher education?

Let’s take a step back and imagine what an ideal university is like. Does it have LGBTQ organisations? Does it support diversity as a principle? Does it have a delegation at the Pride parade? Does it make it possible to raise academic questions – through theses, research, publications, or presentations – on LGBTQ issues? Does it host LGBTQ-themed events and programmes? Well, this is all true for the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, where we currently work/study, and we feel it is indeed ideal in many respects. We feel safe and free to be ourselves. Despite this we cannot claim it is “the best of all worlds” for an LGBTQ person, for there is still a lot of ignorance and we can feel the chilling breeze of the growing far right on our cheeks even here in one of the most tolerant countries of the world.

As we wrote earlier, in our Norwegian class at university, we both did the obligatory presentation on LGBTQ issues in Norway. Amy focused on rainbow families – and this inspired our newly launched article series – and Anna scrutinised university life. This article is a summary of the latter (but if you are interested, you can view the full presentation in Prezi here). Our choice of concentrating on LGBTQ issues was motivated by the fact that, although Norway is an accepting country and we spend most of our time at one of the largest universities in Scandinavia, we have often found that our surroundings are still confused about our identity and our relationship. It was most often when we interacted with foreigners, and truth be told Norway and NTNU has a large number of immigrants, many of whom come from countries hostile to LGBTQ eights. Therefore, we felt we had to take the opportunity to sensitise our – typically heterosexual – peers at the university.

Organisations

To explore what it’s like to be LGBTQ in higher education, we spoke to representatives of two LGBTQ organisations on campus. The student organisation, Skeive Studenter (meaning “queer students”), organises several events a month for bachelor’s and master’s students (in Norway, a PhD student is not considered a student, but an employee). Among other things, Norwegian and foreign students at the university can choose from a variety of activities, including game nights, film screenings, talks and excursions. According to the students interviewed, an inclusive and active community has developed around the programmes, which has shaped the lives of many of them. The university does not provide any financial support to the organisation, but FRI, the LGBTQ umbrella organisation in the country, provides an annual budget to cover minimum costs.

In addition to the student group, there is an organisation for staff too, the LHBT Ansattenettverk (ie. the LGBT employee network). This organisation does not receive any funding from the university either – despite the fact that many employee-led organisations have an annual budget thanks to the university – and there is no national umbrella organisation behind this network either. So the group has zero budget. In addition to internal, members-only events such as dinners, the team also organises public events open to the whole university community. Anna was one of the participants in the most recent panel discussion, which focused on the challenges of (transnational) LGBTQ careers in academia.

Visibility

While it is commendable that there are LGBTQ organisations on campus, it should be pointed out that the university does not actually do much for the community. For a start, there is no financial support for such organisations, which translates to little visibility and awareness. For example, it is not easy to find out that such organisations exist on campus at all. There is hardly any sign on campus that the university is supposedly LGBTQ-friendly. True to its declared values, the agreement has been that the university would display the rainbow flag during the local Pride (which in Trondheim is the first week of September, precisely so that the large student population can be present). However, this is forgotten year after year. Last time, when the authorities were asked for an explanation, the answer was that they only wanted to display it on the day of the Pride parade – which is always on Saturday, ie. when no one is on campus to see the flag.

Challenges with gender

In addition to the issue of visibility, there is also the challenge that the conscious use of pronouns by teachers, ie. primary role models, is yet to become a common practice. In Norwegian, the third person singular pronoun is gendered: hun for female, han for male, and more recently hen, taken from Swedish, and de, inspired by the English singular they, have appeared as non-binary pronouns. Students resent the fact that many teachers fail to set an example, whether in email signatures or in self-introductions in the classroom, to declare their preferred pronouns. This could set a precedent for students, while also raising awareness of the LGBTQ. In the case of toilets, many complain that there are few non-binary restrooms, and that there are few toilets for women in STEM buildings. The use of language that normalises gender stereotypes, especially in science and engineering programmes, is also a recurring problem.

In summary, Norway is way ahead of Orbán’s Hungary in terms of LGBTQ rights and acceptance. Therefore, it is not surprising that one can feel better as an LGBTQ person in a Norwegian university than in Hungarian higher education. After all, in Norway it is possible to talk about LGBTQ issues, which even includes doing research on such topics. Even more importantly, acceptance and tolerance for diversity is a principle, and as such one does not need to fear being beaten up for a rainbow tote bag or badge.

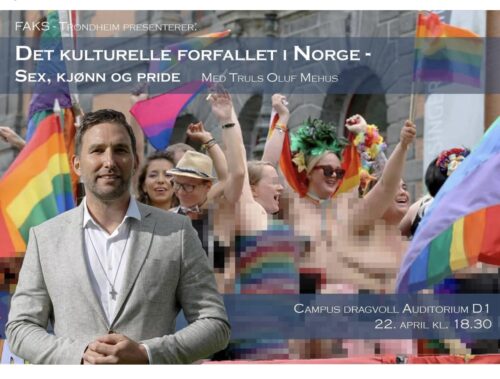

But the spread of the far right is evident even in Norway, especially regarding non-binary and trans issues, and this has become apparent in higher education as well. To give just two examples, the LGBTQ-themed presentation described above did not receive a clearly positive response from the Norwegian teacher, even if they could not officially object to the topic. Moreover, it happened a few weeks ago that, despite student and faculty protests and the university’s past practices, an event portraying the LGBTQ as “propaganda” and “the ruin of the nation” got the green light. Such rhetoric is all too familiar to us from the Hungarian political discourse.

The need for LGBTQ communities to come together internationally is once again very topical.